Esther (Bible Story Summary in bulletin here)

Who are we? What makes us who we are? How do we know who we are and not forget? These are big questions, and the answers matter.

Right now our country is in the midst of these question on a large scale, which we saw played out this weekend in striking contrast of parade and protest, violence and voices, and at the moment, all eyes are on Minnesota at the moment as we reckon with political assassination – something that seemed like an ‘them, over there’ thing until it because an ‘us, here’ thing yesterday. Is that who we are now?

I attended two funerals this weekend, and funerals also try to answer these questions. Most funerals wrestle pretty directly with our two big questions, Who is this God and what is God up to? And what is a good life and how do we live it? This weekend I heard that God is love, and Jesus came to share this life with us and overcome death, so that the separation of death we suffer now will not have the final word. And I heard stories of two very different lives, both lived well, lives woven into other lives with love, and lived for something bigger than themselves.

How do we know who we are? How do we figure out what is God up to? What makes a life good, and how do we live well? These are not solo questions. We do not ask them alone. Faith is not an independent, self-directed thing. Neither is identity. We do not decide on our own who we will be. We get to explore and become, alongside people who see us and reflect back to us who they see us becoming, and encourage us in our exploring. We are always in context.

To understand our context we use stories. The stories told at funerals and around the tables afterwards, describing scenes and moments, show us who people are, wonders what makes them that way, and so probe against the question of what a lifetime is for, and how to live it well. Stories tell us where we came from, and reveal how people before us navigated their lives. Stories help us to know who we are.

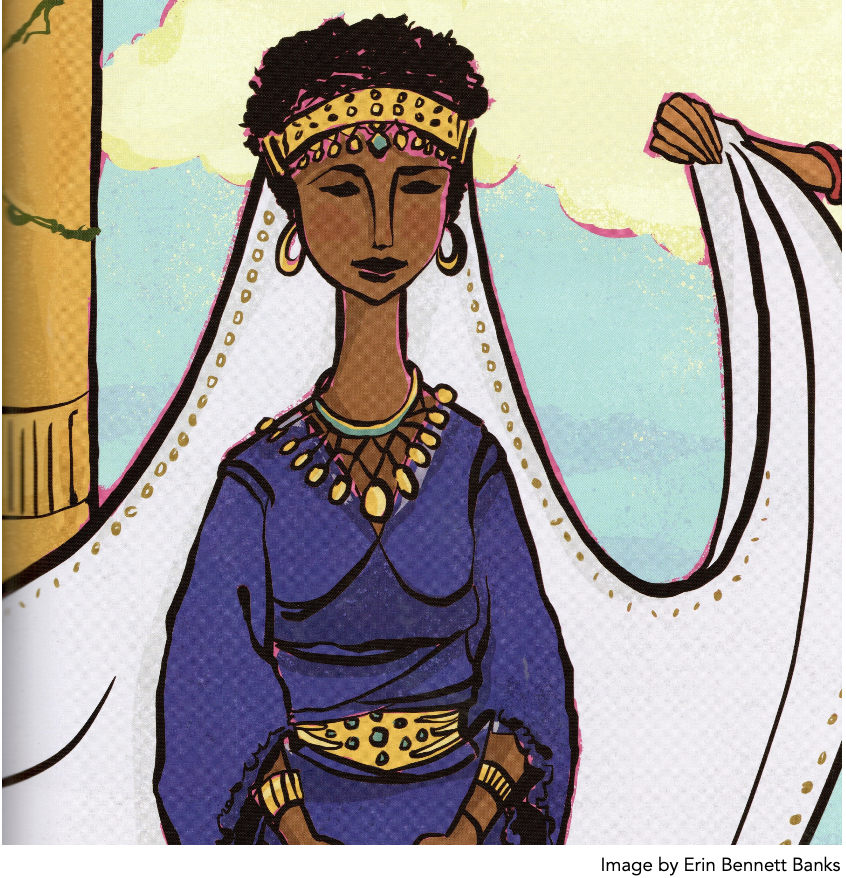

Reading the story of Esther on Purim grounds the Jewish people in their identity and context. Here was a time when they could’ve all been exterminated, and instead they were delivered. Here is another story of a Jewish person living in the royal court of their oppressors, like Daniel in Babylon, and Moses raised up by the Egyptian princess, and Joseph in Egypt before him. Here is the story of a young woman whose courage to speak up saved her entire people throughout the whole empire. But she did not have that courage all on her own. She said to Mordecai, “Have all the Jews pray and fast for me for three days, then I will go speak to the king, even though by doing so I may die.”

But instead of dying for approaching the king without permission, Esther’s request was heard, and the people were saved, and Haman was destroyed instead. Mordecai himself announced the day of Purim should be celebrated, and so it still is.

In telling it again and again, year after year, Haman becomes the representative of all anti-semites, and Esther is the paragon of courage. The story tells of this scattered and weak people, who by the hand of God, outlasted the Persian empire that almost wiped them out, and the Babylonian and Assyrian and Egyptian empires before that, and the Roman and Greek empires after it. You come from somewhere! It says. You belong to something! Telling it again and again together, with food and ritual and songs and symbols and sounds and sharing with others and giving to the poor, helps to ground them in the truth of who they are and keep practicing who they are called to be. And it helps them watch for where God might be calling them to act now. Because in the book of Esther, God is not front and center. The people have to wrestle, and discern, and choose, and act, without some of the flashier directness God uses in other parts of scripture. So, it feels like the kind of discernment we modern people have to do too, when we hear Mordecai wonder if God might have allowed Esther to be in her position “for such a time as this.” And this ancient scroll drops that phrase into words the first time in human history. “For such a time as this” is the kind of line that blows open our imaginations, yanks us from our self-defined ruts and the constraints of what is – and propels us into the possibility that we’re actually living in a broader story, not dictated solely by what we can see, a cosmic timelessness that lands in time at certain points and calls us to respond.

In a little while we will gather at the communion table and we will hear the words of Jesus – the very words Jesus spoke over 2000 years ago, when he invited his disciples and so invites us all these centuries later – to come to this table, and share this bread and this cup – that this is his body and blood shared for us, his very life given for our life, drawing us into life that will not end.

How do we know who we are? How do we figure out what is God up to? What makes a life good, and how do we live well?

Do this in remembrance of me, Jesus says. Come back to who we are together. You are not alone and apart. You are part of me and joined together as a people claimed for God’s way and defined by God’s love.

Our identity is not our own. We are in Christ. That means that we have died his death and been raised into his life, and this life that cannot die is what defines us. Sin says we are apart and against, we must earn our belonging and we can refuse others’ theirs, we have to hide in shame when we mess up and strive to make our life valuable on our own, but we are dead to sin. All need for fear and self-protection has died with Christ. All our losses and pain are not ours alone to hold, we are held together by God in the hands and hearts of other people. Christ’s complete belonging to God and all others is given to us. That is who we are. Beloved Children of God, each one of us uniquely made and directly called to participate in and share God’s love. And we come from a community of those who’ve died and been risen to freedom and hope. This identity is unshakable and secure, because God decides it is so.

But sin is loud and fear’s voice is persuasive. We forget who we are. So when we come to this table, it is like sitting down to eat with all those gone before, and all those right now around the whole world who are also in this community of the died and risen One, whose lives are part of Jesus’ life, and who live as a people claimed for God’s way and defined by God’s love.

Then we do what Jesus told us to do at this table, but we also retell the story. We remember how it began, and this remembering together and practicing together, helps us remember and practice being who we are right now, with courage and hope, and helps us look forward to the day when what we are practicing for becomes the full reality forever.

Today we prayed a blessing on our high school graduates. As they keep asking the questions that human lives are shaped around, How do I know who I am? How do I figure out what is God up to? What makes a life good, and how do I live well? Their immediate context will change but their larger context remains the same. The somewhere and someone they come from is not just their families and friends, it’s us, but not only the little LNPC us here and now, the big us. They come from a story that reaches back to the beginning of time and forward beyond time, a story shared in ritual and rhythms, in relationships and in remembering. They come from Esther, and Joseph, and Ruth, and Samuel, and Jacob, and Hagar, and Moses, and Mary and Joseph, and all the followers of Jesus who had no clue what they were doing but followed anyway and God took care of them and invited them to join in what God was up to anyway. They come from these stories practiced in candlelit Christmas eves, and finding Easter Hallelujahs and being served communion by the person next to you, and most importantly, praying and being prayed for. Watching other people struggle with suffering and sadness, and holding them up to God. Knowing other people are holding you up to God because they’ve literally sung “God in your loving mercy hear our prayer” about something you just named aloud.

When Esther was faced with something impossible, something terrifying, with huge consequences – it could maybe save her whole people? Or she could maybe die? – she said, ask everyone to pray for me, and I will do it.

When you belong to the people of God, you are not alone. The people of God are people of prayer, people who help each other remember it is God who saves, and it is God who acts, and it is we who join in, we who get to be part of the action and the saving that God is doing. These people are here in this room, and these people are everywhere. Your community is vast.

We live short lives inside a long story. Empires rise and empires fall, but God is constant. This is our context. The people we love live their good lives and then die, and we miss them, and then we tell stories to help us know who they were, and know who we are because of them, and help us figure out what makes a good life and how we might live, and watch for what God is up to in all of this. And their life goes on beyond what we remember and so we remember that ours will too.

As we bump along our own lives, mostly doing our best and making it up as we go, we are held in a web of story, and prayer, and remembering, and retelling. That is how we keep bravely asking the human questions, and this is how our identity is shaped and held.

Who we are is the people who’ve died to death and been raised to life, who practice being available to God and letting God’s love and healing come through us. And in the cosmic timelessness of Jesus Christ, our lives are always for such a time as this.

Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment