Mary

This is the famous scene, the angel’s pronouncement, which the church has called, “The Annunciation.”

Denise Levertov’s poem, Annunciation, asks,

Aren’t there annunciations

of one sort or another

in most lives?

Some unwillingly

undertake great destinies,

enact them in sullen pride,

uncomprehending.

More often

those moments,

when roads of light and storm

open from darkness in a man or woman,

are turned away from

in dread, in a wave of weakness, in despair

and with relief.

Ordinary lives continue.

God does not smite them.

But the gates close, the pathway vanishes.

The suggestion that we all have moments of divine invitation to be part of something more feels like a stretch sometimes. In a week where I have spent more time than I care to admit being, as my kids call me, a “Karen,” (which apparently means someone who always asks to speak to a manager), in my case, trying to sort out delivery issues for a bed that has twice been in a truck on its way to my house but still has not arrived, between fighting a head cold, scraping my windshield and shoveling my driveway, juggling work, and parenting, and making dinner, and Christmas shopping, and ending most evenings watching the news in open-mouthed horror, this week it feels a bit farfetched for me to imagine being invited by the divine into something extraordinary.

But imagine this is true. Imagine that we are. (Because it is. We are).

Imagine for a moment how we might greet these annunciations.

Lots of people, this poem suggests, do great and valuable things in life without any awareness of or appreciation for it. They go through life unaffected, oblivious to the conspiracy of redemption unfolding around, and indeed even sometimes through, their own lives.

Others come to their annunciation moments with definite awareness, and so also fear and trembling at the terrible toll that risking will likely take on their equilibrium. They back slowly away from the moment of change and choice, turn away and sit back down in their perpetual risklessness, preferring the delusion of safety, the illusion of inertia, to reckless trust. And those people don’t get to be part of the marvelous things beckoning them to life.

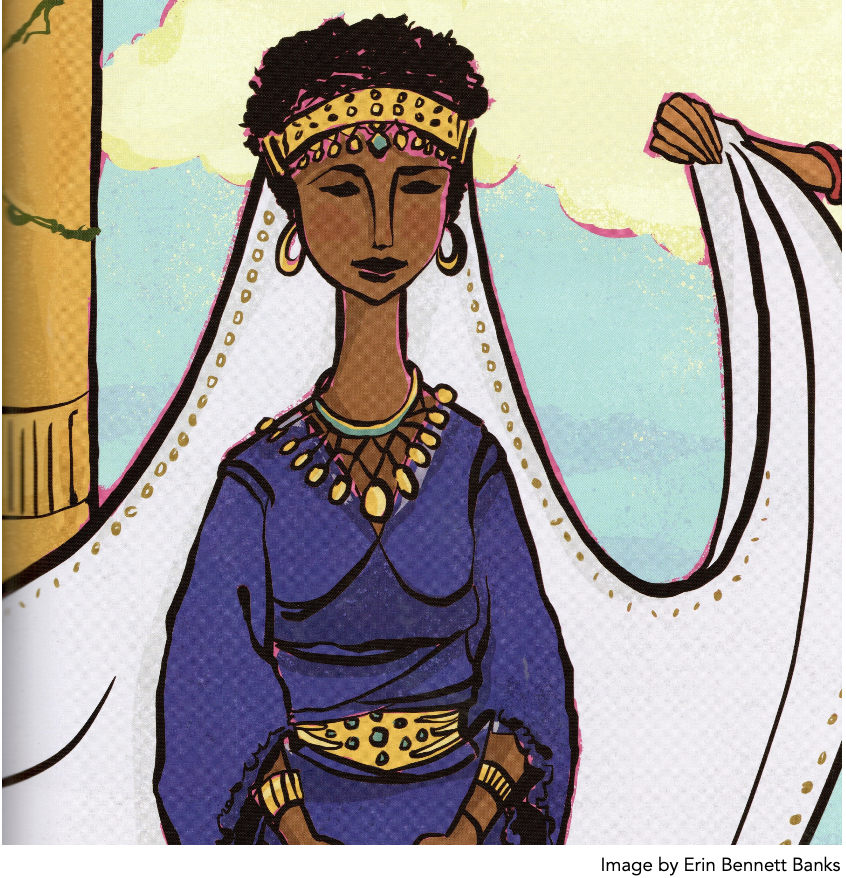

But Mary. She was open and ready when God’s Yes came.

God said, I am about to do the unfathomable. You, Mary, will be in this with me. And she met the moment with her heart open. She saw it for what it was, and she heard the Angel Gabriel when he told her, “Do not be afraid.”

What is it to say Yes to God’s yes?

To meet your annunciations when they come?

To allow yourself to take them in - to be taken in - with bewilderment, curiosity, willingness, and courage?

How can this be? Mary asks, explaining to her celestial visitor the biological impossibility of the thing he is announcing. It is impossible.

But impossibility is how God always chooses to come.

So the angel tells her about Elizabeth.

He could have told her about any of the barren wombs or stuttering spokespeople, dead seas or impenetrable walls, invincible armies or lions’ dens, enormous giants, weak-minded monarchs, messed up protagonists, or hopeless, impossible situations through which God had been bringing salvation and hope to the world since the world began. But he doesn’t look back for his stories. Instead, he says, Right now, even while we are speaking, God is doing this impossible thing.

And then the angel tells her about old Elizabeth, whose prayers had dried up, who is even now already bearing this great in-breaking of salvation.

Nothing is impossible for God, Gabriel answers Mary.

And Mary says Yes. She says Yes to becoming the Mother of God.

There’s a saying in NVC – non-violent communication, that we’ve studied a bit around here – that every No is a Yes to something else. When someone tells you No, they are saying yes to another thing – whether they are needing space, or autonomy, or agency or have made other plans with someone else - there is always a Yes somewhere inside the No.

I want to suggest the opposite is true as well, for us finite creatures. There is always a No inside our Yeses. When we say Yes to something, we are saying No to other things – every other option, in fact. Yes to chicken means we’re not having chili. Yes to marrying this person means No more living life completely on my own terms.

When we say Yes, especially to God, we are called to renounce something. We must let something go. That’s how love works. Something we’ve thought our life would be or already was, some illusions about control and invincibility, we must sacrifice something of ourselves, something must die.

Most often what dies was not really giving us life to begin with, we only thought it was. But sometimes we are called to let go of good things. Things that are giving us a good life, making us happy and stable.

Mary was engaged to a kind and decent man, about to start her life. A good life. A happy, ordinary, stable life. And when she says Yes to God, all that disappears. Like Elizabeth whose retirement will be invaded by a fiery prophet child, like Hannah long before them, who gave up her own child to God and Samuel became the prophet who lead God’s people, Mary is being pulled into God’s redemption of the world, and it means she is no longer going to be who she was. The Annunciation could very well be called The Renunciation. Gone is the life she had embraced for herself, the path so neatly laid out before her, she renounces it here.

Jan Richardson’s poem, Gabriel’s Annunciation, begins with these words,

For a moment,

I hesitated,

on the threshold,

For the space

of a breath

I paused

unwilling to disturb

her last ordinary moment,

knowing that the next step,

would cleave her life,

that this day,

would slice her story

in two

dividing all the days before

from all the ones

to come

How vulnerable it is to let go of all that gave your life meaning and purpose and order and jump into the unknown like this! But she does, she lets all of it go in order to participate with God in something bigger.

Hannah went in eyes wide open and offered her renunciation before even the gift arrived. But Mary, perhaps she didn’t fully grasp all that she was letting go of, the predictable and most likely mostly pleasant life she would never live from then on out.

She traded it away without knowing, because how can we know what our Yeses will mean until we’ve already been changed by them? What she traded it for was a life fully alive, she traded it to see God, to be disciple of Jesus. Mary and his brothers were there among the disciples and followers of Christ, listening to him tell about God’s salvation, watching people be healed, seeing the power of God at work in the world. Mary watched her child die a terrible death, and she spoke to the angels sitting aside an empty tomb. She was in the room when the Holy Spirit came, and she was a leader in the early church.

Don’t be afraid, the angel says. Not because suddenly everything will be steady and safe. It’s decidedly not safe, and it’s most certainly not steady. It’s absolutely risky and will for sure change everything. Don’t be afraid because the one who calls you is God. You are held in God’s love, joined in God’s purposes.

But Mary is not the only one vulnerable here. Imagine also the vulnerability of God, not only to come into the human experience, weak and helpless, at the mercy and in the hands of those you’ve created, preparing to live, and die as they do. But God also takes on the vulnerability inherent in love, the possibility of rejection. Mary could have said No.

We’re at something of a deficit here, when it comes to our own annunciations. Before we even get to the question of renunciation and trust, we must first accept that God is real, that God is doing something greater, and that God might interrupt our lives and call us into it.

So perhaps the word for you this week is simply this, What would it be to go through your week assuming God is alive and active in the world?

What if you lived this week like this is true?

And certainly, this is enough for any of us, because most of us, most of the time, either deny, ignore, or forget that God is real. What if this week you sought to consciously remember?

But let’s go one step farther, if you’re willing, and say, not only is God alive and active in the world, God is inviting you – specifically you – to participate in God’s schemes. You don’t know when or how the invitation will come, but your annunciation, that is, your belovedness and chosenness in God for a purpose, is as real for you as it was for Mary. Greetings favored one; the Lord is with you!

You won’t be called to carry the actual Christ-child; that role has been taken. But to live a God-bearing life? That is a role you share with Mary. There will be specific callings just for you within that role. People who come across your path, a phone call, a question, an opportunity you will recognize, a vulnerability you’re invited to share.

More than Mary, even, we are drawn into the very life of Christ – we are invited to life in Christ, a life, C.S. Lewis reminds us, that is “begotten, not made, that has always existed and always will exist.” We will be drawn into life that doesn't end, life inside the love and connection between Jesus and the Father; and life with the Holy Spirit interfering and leading. The God-bearing life is Jesus’ life lived through ours, our hands and feet and voice, our words and actions.

Will your moments be lived be grudgingly or unaware? Will you recognize the cost and back away from the invitation? Or will you open your heart and life and join in what God is wanting to do through you?

Most likely, and most often, it will be to see another person in their humanity and minister to them, or to receive ministry from another person. This is who God is and how God comes, as a minister, and as one in need of ministry, and so it is how we experience God in our lives as well. We bear each other’s burdens and share each others joys, knowing that when we do so, we are joining in what God is already doing – we are where God is.

Immediately after the Angel’s annunciation to Mary, she goes to Elizabeth. When Mary hears that Elizabeth too is pregnant with an impossibility, she makes a beeline for the one person who will understand and can share this with her. And when Elizabeth sees Mary, little fetus John the Prophet in her womb does joyful summersaults, and Elizabeth just knows, without Mary saying a thing, what it means. So Elizabeth prophesies, saying, “Who am I that the Mother of God should come to me?”

And then Mary, having been seen, having had this whole crazy thing confirmed right to her face, breaks out in a prophesy of her own, that has come to be known as the Magnificat,which we sang earlier, about what God is doing to set the world right.

It is not until they share this mystery with each other that they can live into it fully themselves, and I think that’s what it means to be Church.

We do not say Yes to God alone – we are given each other, given to each other, and there we find God – in words and acts of healing and hope that pull us out of ourselves and the minutia of our self-absorbed worlds, or out of our fear about the general state of things, and into action, along with the God who is already always acting.

So, perhaps your call this week is to imagine God is alive and active.

Or perhaps it is to anticipate annunciation and say Yes when it comes. Or maybe, it is to step into your own renunciations and let go of what keeps you from Yes. In any case, you are held in God’s love, joined in God’s purposes.

Just a few months after the annunciation, when she delivers this baby and brings God into the world as a tiny, needy, human child – before priests from a far off land come to meet the baby, before she and Joseph flee to Egypt with the baby, before the potty-training, and the talkback, and the teen years – that night, lying in the hay with Joseph by her side, just after placing the sleeping child into the manger, the stable, already crowded with animals, is suddenly invaded by a group of shepherds from a nearby hillside.

They tell Mary about their own annunciation. They tell her about a sky full of music and light, about the Angel’s pronouncement that God has come into the human story; God’s Yes to the world is embodied, “Do not be afraid!” the angel had told them, “This is good news of great joy for all people!”

They tell her this when they’ve said Yes to God themselves, and set out to find the baby wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. And then, when they share their story and are received, together they all bear this mystery, they are Church.

And Mary, we are told, treasures their words, and ponders them in her heart. Their words become for her another annunciation, just like Elizabeth’s before them. Mary continues, her whole life long, to open her heart to God’s pronouncements of love and invitations to involvement. And the rest of her life she keeps agreeing to be in this with God. And for the rest of her life, she is.

The God who does impossible things is even now, right this moment, doing impossible things in the world. This God wants to do impossible things through you. It’s absolutely risky and will for sure change everything. You will be vulnerable, and you will have to let things go that you thought you needed.

But, Don’t be afraid, because the one who calls you is God. And what you’re saying Yes to is to see God, to be disciple of Jesus, to live a life fully alive. And this mystery is lived by sharing it, so you wont be asked to do it alone.

Amen.

(*This is an older message about David, in this series, we had a wonderful performance of 'David" by Theater for the Thirsty)